The dangers of the Single Global Process

August 12, 2019

There are a few things in the Elixir/Erlang ecosystem that I consider required reading. To spawn, or not to spawn? by Saša Jurić is definitely one of them. If you haven’t read it, you need to. It’ll change the way you think about building elixir applications.

Seriously go read it.

That post flipped the elixir communities’ idea of good design on its head and for a good reason. Modeling the domain with pure functions is a powerful approach and one that we should strive for when we can.

But, there was one pattern that emerged that I think has been misapplied as a universal solution. That pattern is what I’ve been calling - for lack of a better name - the “single global process” pattern or SGP for short. You’ve probably seen this pattern. Its the one where you do this elegant, functional domain modeling and then put it in a long-running process somewhere, effectively turning the process into a write-through cache. In Saša’s post, the single process is the RoundServer.

I don’t think Saša intended to promote this pattern. I wasn’t there when he was writing it, but I always thought that using a single RoundServer to manage a round was somewhat incidental. The unique process was an implementation detail, and the critical point was to model your domain with functions.

Because here’s the thing. The SGP pattern introduces a ton of problems. Problems that you, dear reader, are going to need to solve. In my experience, the SGP is one of the most intricate patterns you can introduce to your system despite being one of the easiest to build. I’m going to do my best to convince you of this by enumerating several of the problems that you’ll face as well as some potential solutions.

The Setup

To drive these points home, we need a motivating example. I want to focus on the runtime concerns, so I’m going to reduce our problem domain to a simple counter. Here’s our functional core:

defmodule Counter do

def new(initial \\ 0) do

%{ops: [], initial: initial}

end

def incr(%{ops: ops}=counter) do

%{counter | ops: [{:incr, 1} | ops]}

end

def decr(%{ops: ops}=counter) do

%{counter | ops: [{:decr, 1} | ops]}

end

def count(%{ops: ops, initial: init}) do

Enum.reduce ops, init, fn op, count ->

case op do

{:incr, val} ->

count + val

{:decr, val} ->

count - val

end

end

end

end

To update a count we “cons” increment and decrement operations onto a growing list. When we want to find the actual count, we fold over the list either incrementing or decrementing starting from some initial value.

For the server, we’ll use a GenServer.

defmodule CounterServer do

use GenServer

def start_link(opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, opts, name: Keyword.get(opts, :name))

end

def increment(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :incr)

end

def decrement(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :decr)

end

def count(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :get_count)

end

def init(_opts) do

{:ok, Counter.new()}

end

def handle_call(:incr, _from, counter) do

{:reply, :ok, Counter.incr(counter)}

end

def handle_call(:decr, _from, counter) do

{:reply, :ok, Counter.decr(counter)}

end

def handle_call(:get_count, _from, counter) do

{:reply, Counter.count(counter), counter}

end

end

The server is equally trivial. It manages the lifecycle of a counter in response to calls. Unique counter servers can be started like so:

CounterServer.start_link(name: :some_fancy_counter)

With these pieces finished, we have a good starting point to discuss problems with this design.

The problem

What we have so far seems pretty good. And if all you really needed were a simple, in-memory counter, this would probably do the trick. But this is a contrived domain that I’ve intentionally kept simple, so I can focus on other things. Typically the state we deal with is essential. The data that makes up most company’s core domain is not ephemeral. People will make decisions based on these data that we’re working with. That means these data needs to be persisted. So let’s add persistence. If persisting a counter to a database bothers you, then you can tell yourself that the counter is used to bill clients for the use of your API or something.

The typical recommendation for persistence is to initialize the process with state from the database. When the process receives a message to write or update its internal state. These updates are applied to our internal data and then persisted. Utilizing the SGP pattern, any read requests can come directly out of memory saving yourself the database roundtrip. Let’s update our Counter Server to reflect this change:

defmodule CounterServer do

use GenServer

def start_link(opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, opts, name: Keyword.get(opts, :name))

end

def increment(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :incr)

end

def decrement(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :decr)

end

def count(name) do

GenServer.call(name, :get_count)

end

def init(_opts) do

data = %{

counter: nil,

name: opts[:name],

}

{:ok, data, {:continue, :load_state}}

end

def handle_continue(:load_state, data) do

{:ok, initial} = get_from_db(data.name)

{:noreply, %{data | counter: Counter.new(initial)}}

end

def handle_call(:incr, _from, data) do

new_counter = Counter.incr(data.counter)

:ok = put_in_db(data.name, new_counter)

{:reply, :ok, %{data | counter: new_counter}}

end

def handle_call(:decr, _from, data) do

new_counter = Counter.decr(data.counter)

:ok = put_in_db(data.name, new_counter)

{:reply, :ok, %{data | counter: new_counter}}

end

def handle_call(:get_count, _from, data) do

{:reply, Counter.count(data.counter), data}

end

end

When the counter process starts, we load the state in a handle_continue callback. If we receive an increment or decrement message, we update the counter and shove the new counter into the database. Reads are returned from our in-memory representation saving us that database call.

This seems great! And it is great - right up until you need to run on more than one node. There are systems in the world that can get by running a single node and maybe your company is one of them. But most companies end up needing to run more than one node at some point whether for resiliency or to handle scale. Most of the time, we run both of these nodes behind a load balancer.

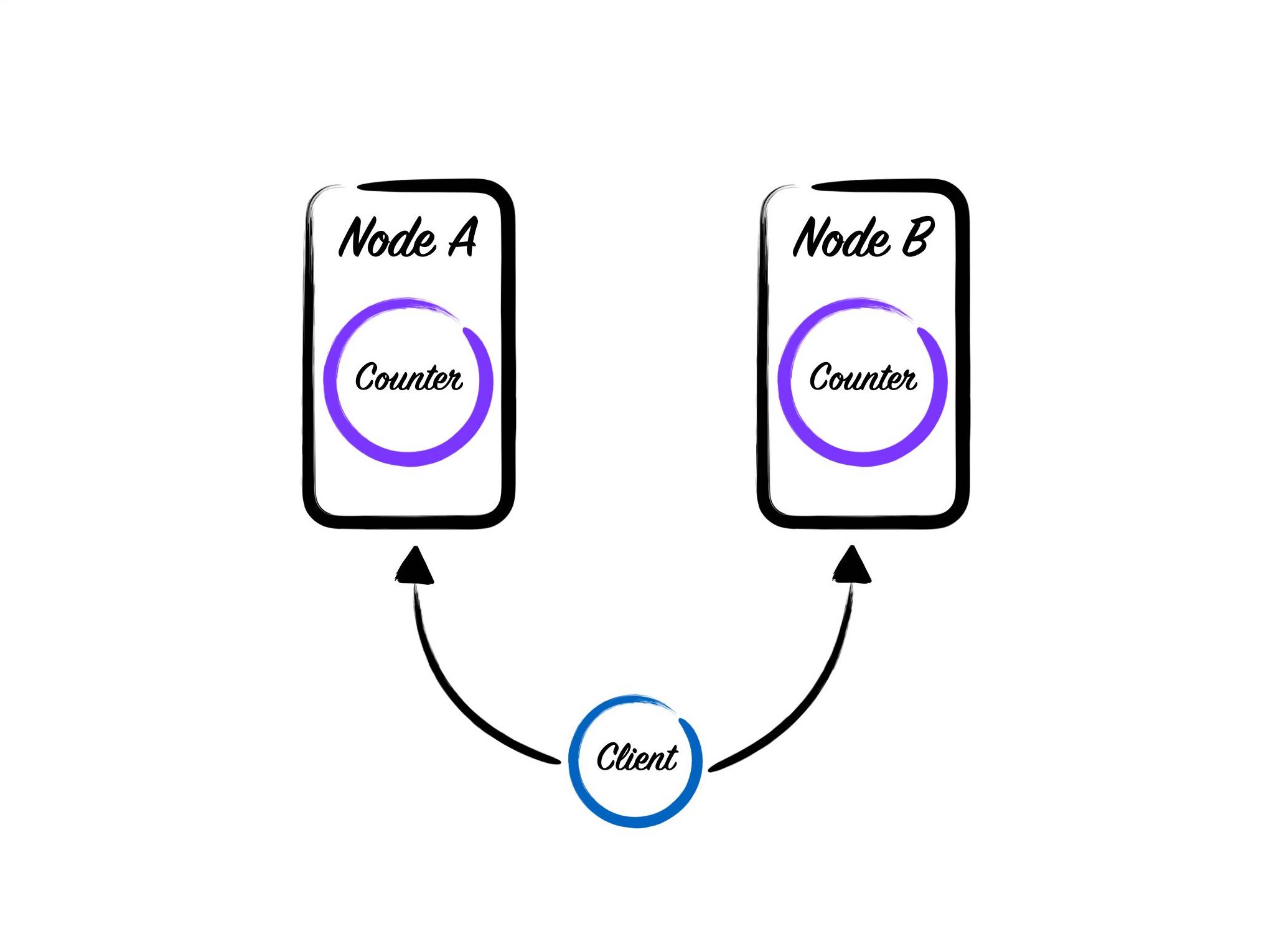

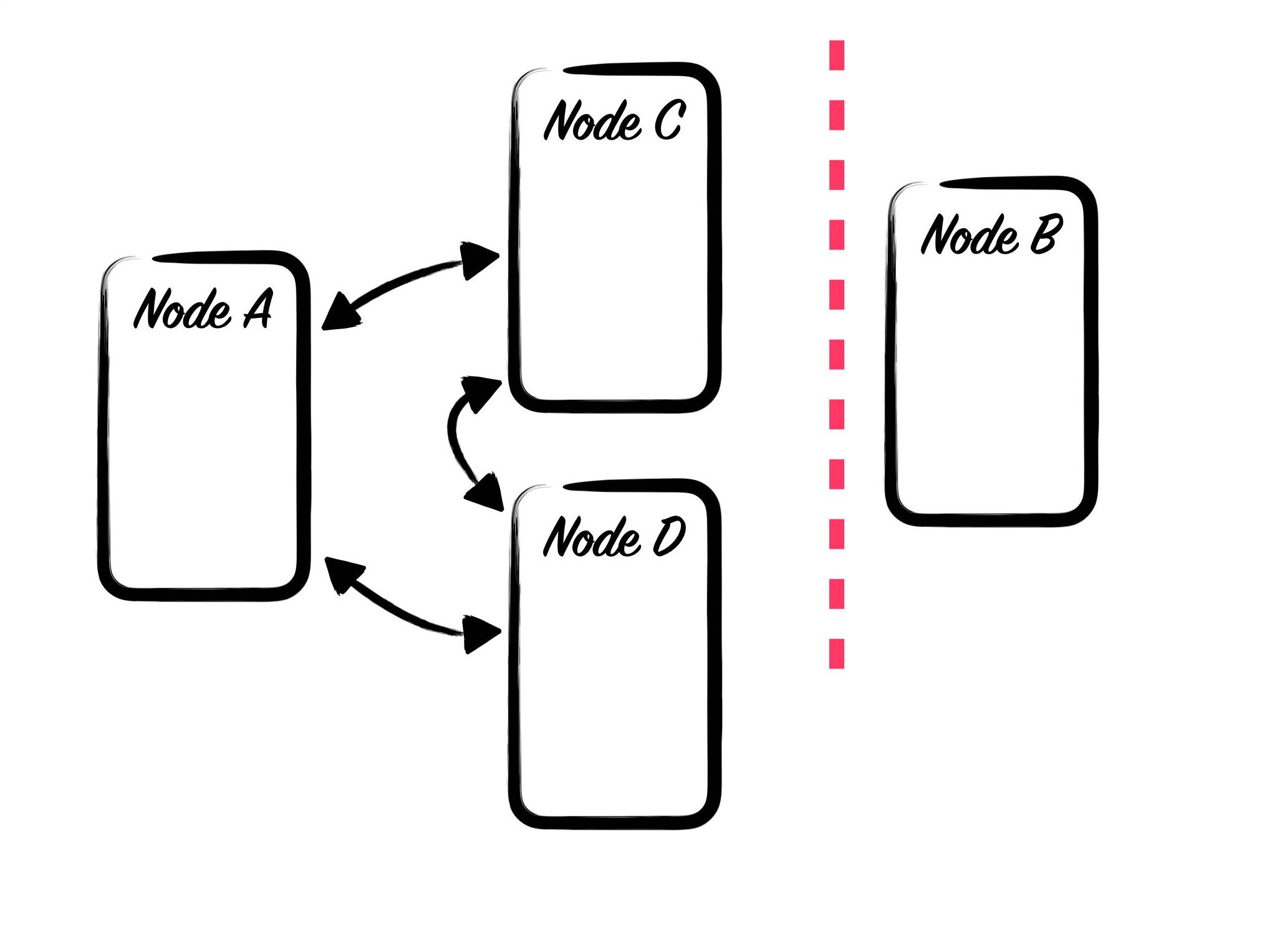

We’ve hit our first problem. The counter we’ve created is node-local. Assuming that we start these counters on demand, it’s only a matter of time before we end up with duplicate counters on both of our nodes.

If this situation occurs, then we have a high likelihood of returning incorrect counts from memory because we can’t know if another node has updated the counter in the database. We also have a high probability of overwriting the previously stored values, which means we have a high likelihood of losing data.

A quick aside about data integrity. Inconsistent data issues are some of the evilest bugs you’ll encounter when working with distributed systems. Bugs like these suck because there’s never a good indication that something is going wrong at the moment it’s happening. There’s no crash or stack trace to look at. Unless you’re constantly monitoring your data integrity, the only way you’ll find out that you have an issue is when you end up charging a client 10,000 dollars or -100 dollars or NaN dollars. There are ways to build eventually consistent systems. But that has to be a conscious choice.

Some partial solutions

There are a few partial solutions to this problem. The ones that I see most people reach for are either persistent connections, sticky sessions, or some combination of the two. Unfortunately, none of these really eliminate the possibility of starting the same counter on two nodes, primarily if more than one user can interact with a counter at a time. Additionally, introducing sticky sessions is a fast way to end up with “hot” nodes due to unfair distribution of work. However, if you can use sticky sessions and are willing to give up on some levels of consistency than this might work for you.

Another partial solution is always to use Compare and Swap (CAS) operations when updating the database. Assuming your database implements a CAS correctly, you can eliminate the possibility of trampling data. But you will still return incorrect values until you do a write or find some other way to get an update from the database.

Neither of these solutions entirely solves the problem, but in conjunction with each other, they might be good enough for your use case.

Distributed Erlang will save us all.

Distribution is always the solution that’s begging for a problem. And there’s no better set of challenges than the ones introduced by an SGP. So let’s indulge ourselves and walk down this path for a bit.

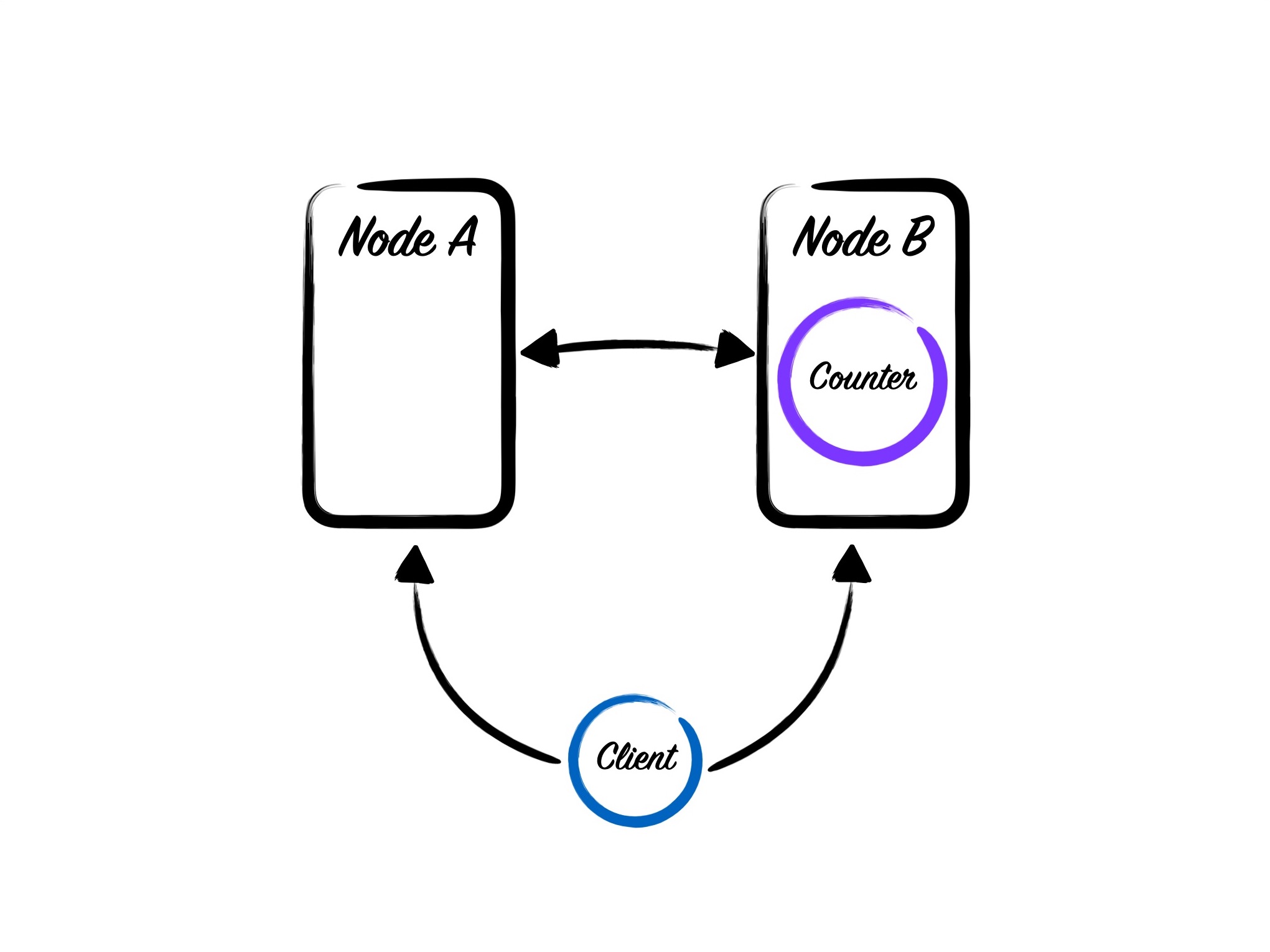

I’ll assume that we’ve found a way to discover and connect our nodes together. Now that we’ve done that we need to register our counters across the cluster. For this example, I’m going to use :global because it’s built into OTP and easy to use. But the failures I’m about to describe are not limited to :global. You can induce these same failures with virtually any of the process registries that exist in elixir and erlang.

Converting our process to use the global registry is straight forward. We need to change the start_link function.

defmodule CounterServer do

def start_link(opts) do

name = Keyword.get(opts, :name)

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, opts, name: {:global, name})

end

end

Now when we want to access our counter, we’ll be able to find it globally regardless of what box we’re connected to.

This solution will work well, at least until we encounter the ever-present specter of distributed systems; the netsplit.

The netsplit bogeyman

Netsplit is a catch-all word that probably gets tossed around to much. I know I’ve been guilty of it. Colloquially it’s used to describe any and all faults that you could see in a distributed system. The odds of seeing a netsplit will depend on your cluster size and the reliability of your network. You’re much more likely to see faults in a 60 node cluster running in kubernetes on amazon’s crappy network then if you’re running 2 bare-metal boxes hard-lined into each other sitting in a co-lo somewhere. But if you run a system for long enough, you’ll eventually see faults. When you see those faults, you need to have a plan for handling inconsistent state - even if that plan is “Fuck it who cares.”

Unfortunately, the SGP doesn’t lend itself to graceful recovery after a netsplit. Let’s talk through some of the issues.

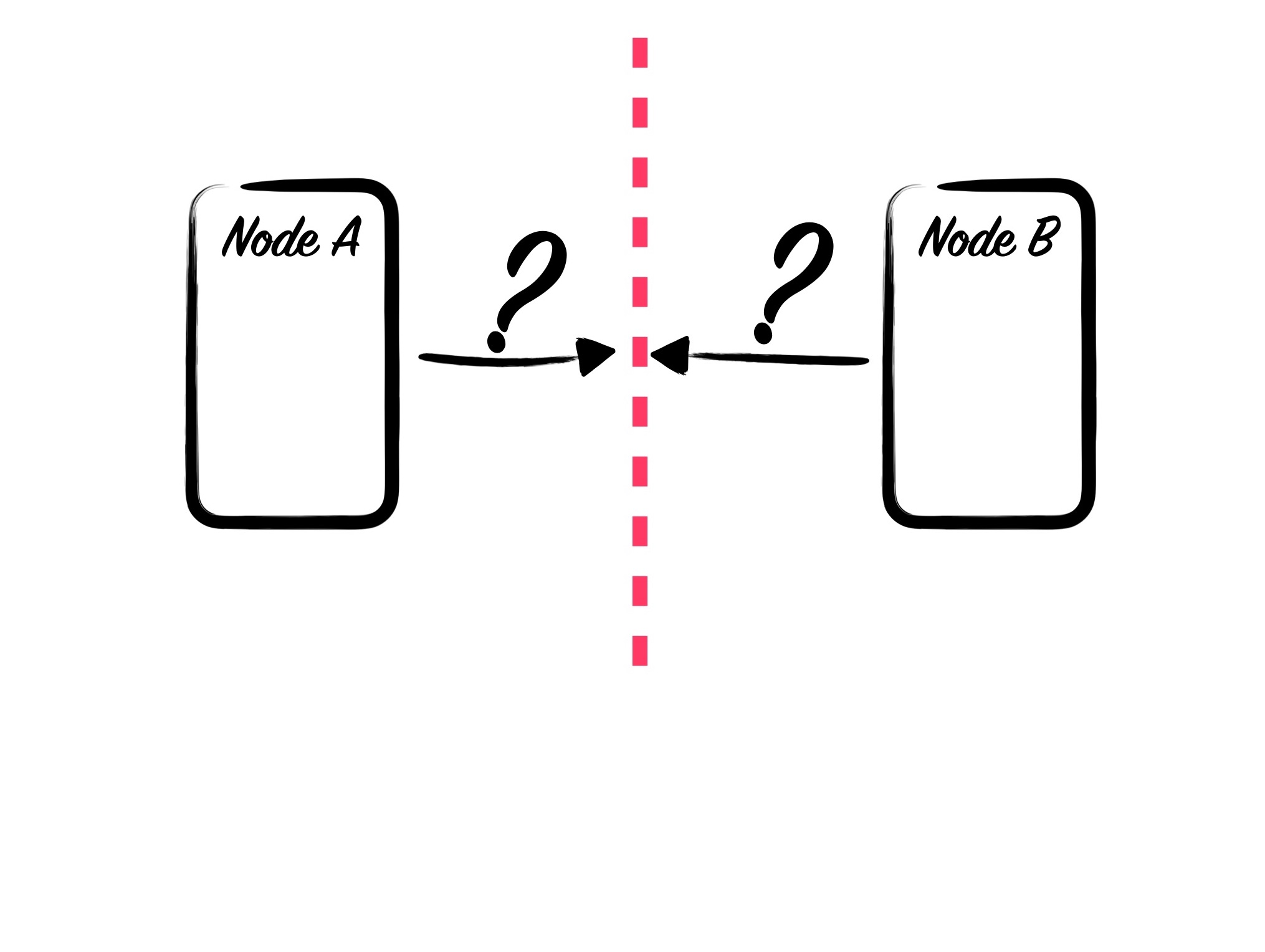

If your boxes have a netsplit, at a high level, it means that 1 of 2 things has happened: a node has shut down expectedly or unexpectedly, or the nodes have disconnected from each other but are all still running. The trick is that from a single node’s point of view you can’t really deduce which it was.

Unless the nodes have a consistent way to talk about cluster membership - Raft, Paxos or similar - all an individual node can really know is “I can no longer talk to these N nodes, and I don’t know why.” This has a secondary effect which happens to make our lives even harder: Deployments and scaling events can start to look identical to netsplits. So while real partitions might be rare, deployments may induce the same failures.

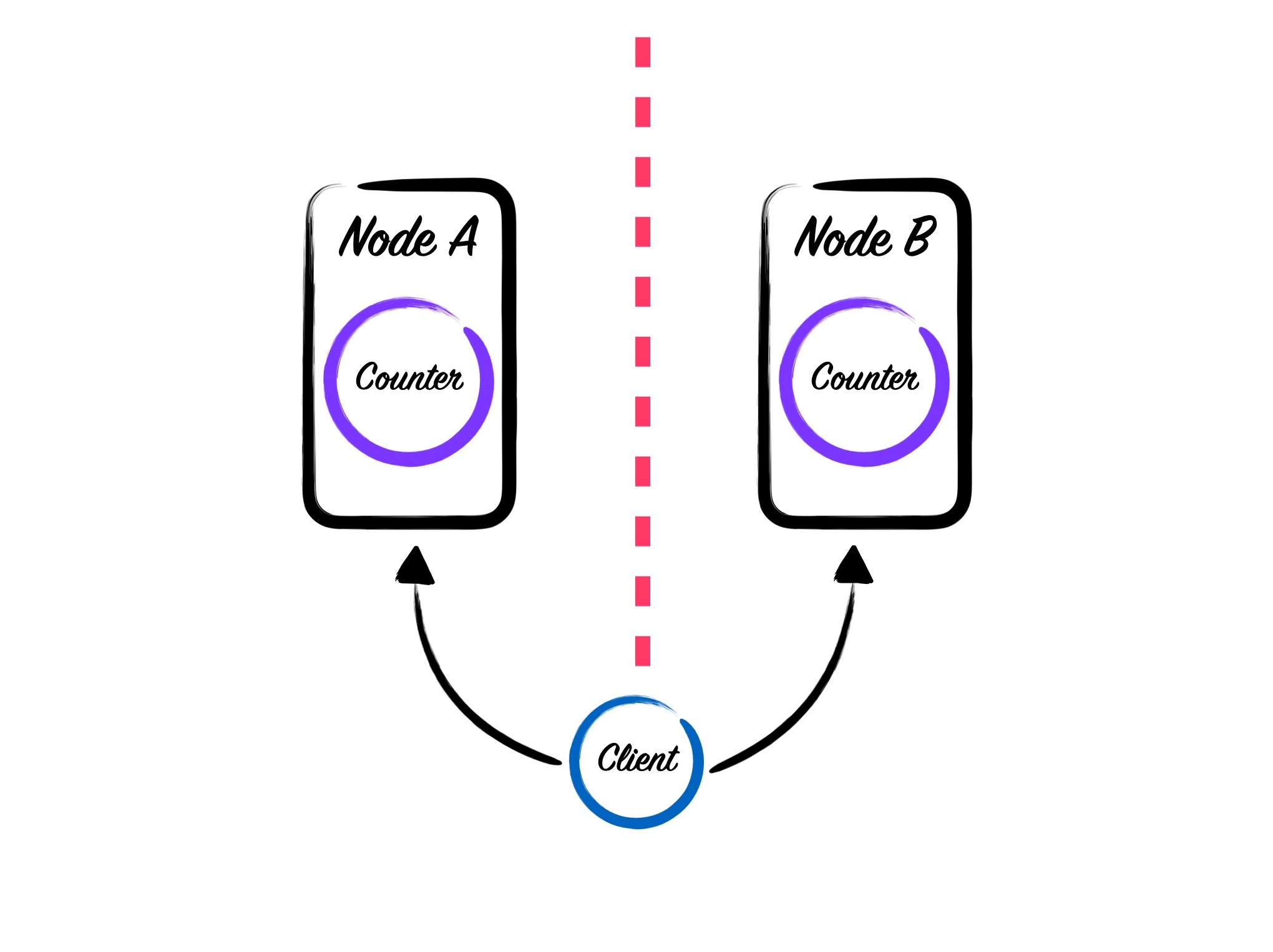

During a partition, the two nodes may not be able to talk. But that doesn’t mean that they aren’t reachable from a client. A client may issue a request, and that request may get load balanced to either node. If the request happens to land on the node that holds the counter, then we’re OK. But if the request ends up on the node that doesn’t hold the counter, we have problems. As I described above the node can’t know if the counter process is truly gone. The default solution is to assume that the process doesn’t exist and start up a new one. We’re back to having 2 counter processes running on separate nodes again!

When the partition heals, we’ll need to reconcile which counter is the canonical one. By default :global discards one at random. Other registries such as Horde give you more control over this reconciliation process. But you’ll still need to take care in how you reconcile this state.

Node monitors will not save you

One of the ways that we can try to solve this is by using node monitors.

:net_kernel.monitor_nodes(true, [:nodedown_reason])

Calling this function in a GenServer will cause node events to be sent to the process as messages. Unfortunately, this isn’t really enough to know the state of your cluster. From any nodes view it’s just not possible to tell if another node has left for good, been autoscaled away, or been disconnected because it couldn’t keep up with health checks.

So how can we solve this? I’m going to focus on three solutions. But there are many others and several variants of each. Hopefully, these will give you some general ideas.

Consistent Hashing and Oracles

Consistent hashing is my default way to solve this problem and is also the most naive. The basic scheme is that you’ll use a consistent hashing algorithm to decide what node a given counter process lives on (Discord has a robust library for this). One caveat to this approach is that during a netsplit your counter process may not be reachable and thus will be unavailable for the duration of the split.

The other caveat is that you need a way to specify the canonical set of nodes in your cluster. We know that we can’t reliably use node events so we’ll need to solve cluster management some other way.

The most straightforward method is to use static clusters. If you need to add new nodes to your cluster, you bring up an entirely new cluster with the new nodes. Once everything is up you can redirect traffic to the new cluster, and you shut down the old cluster. Obviously, this increases the time it takes to deploy and scale, but if you have reasonable scaling needs, this can work well.

If you need to be able to change the cluster size dynamically, then you’re going to have to do more work to control your deploy process. One way to automate this is to issue a specific ClusterChange RPC to all nodes in the cluster. If you go with this route, then you need to ensure that you publish RPCs to each node directly instead of relying on the nodes internal distribution. The reason you can’t rely on the nodes to propagate cluster changes is that if you try to change the cluster during a partition, you can end up in a situation where only half of the cluster knows about the change.

A third solution is to use an external, consistent store to manage cluster state. Most often, this means using something like ETCD or Zookeeper, which can provide high availability, consistent lookups.

In any of these scenarios autoscaling, at least as we typically think of it, is off the table. You’ll need to invest serious time into your deployment and cluster management to pull this off.

CRDTs everywhere

Another way to solve the SGP inconsistency problem is to use CRDTs everywhere. You’ll still get incorrect data during a netsplit, and when persisting data to a durable store, you’ll have to take care not to overwrite data. To avoid this problem, you’ll need to merge the data in your process with the data in the database and then replace what’s in the database using a CAS operation.

CRDTs have a lot of excellent qualities to them, but you need to ensure you are using them correctly. It’s entirely possible to misuse a CRDT and end up in an inconsistent state. Consistency is not a composable property of software. I also strongly advise you not to build your own CRDTs (other than for fun) and instead use something like LASP in production.

If you do decide to go down the CRDT route, you need to be aware that your states may diverge at some point. Each process and the database will have its own view of the world, and those views may all be different. In the fullness of time, you may converge back to a steady-state. But you might not. This is more common in large clusters where your data has a high rate of change. But this divergence can make it very hard to reason about the state of the world.

Just don’t use the SGP

Most of these problems go away if you simply don’t use a single global process to hold your state. This doesn’t mean that you give up on modeling your application as pure functions. Instead, it means giving up on maintaining those data in a long-running process. It’s an easy pattern to reach for and it feels elegant. But you really need to step back and ask yourself why you’re doing this and if you’re ready to solve all of the additional problems this solution will bring. If you only need a cache of values than maybe you’re better off replicating your state to some subset of your nodes instead or building a cache in an ETS table.

If you’re trying to serialize side-effects then maybe you’re better off relying on idempotency and the consistency guarantees of your database. If you like these “event-sourcey” semantics, perhaps you can utilize something like Maestro or Datomic to solve the consistency problems for you. There are ways to maintain similar semantics without incurring the same issues.

When is an SGP ok?

There are always tradeoffs when building software, and there are times when an SGP is a reasonable solution to the problem at hand. For me, this is when the process is short-lived and will mutate no external state. In fact, the other day, I needed to build a search feature. For the feature to work, we needed to gather data from lots of downstream sources and join it all together. The searching was done as the user typed so rather than do the data fetching every time the search query was changed slightly, I did it once, shoved the state in a process, and then was able to quickly search through everything I had already found with very few additional calls required. This pattern worked quite well because I wasn’t trying to execute mutations from inside the process. If the process didn’t receive a message within 15 seconds, it shut itself back down.

I also think SGPs are fine if you genuinely don’t care about the consistency of the data you’re manipulating. That sorta state isn’t the norm in my experience. But it does exist and modeling it in a process this way is reasonable.

Conclusion

I want to re-emphasize that everything in Saša’s post is excellent and I agree with it. If you can design your problem such that you’re mostly manipulating data with pure functions that generally leads to robust systems. I think the problem is how the community has begun to utilize the ideas in that post and not the post itself. I’m also not trying to say that there’s never any place for an SGP. My goal is to demonstrate that while easy to build and conceptually very elegant, the SGP is one of the more complicated patterns you can add to your system. I personally think its a model that is overused in elixir and I don’t believe it should be the default choice. You need to have a good reason to put your state in a single, unique process. Otherwise, you’re probably better served by relying on a database to help enforce your data consistency.

Most importantly if you do decide that an SGP is a right solution for your use case I want you to be aware of the kinds of problems that you’ll face and the types of solutions that you’ll need to work through. If you’re prepared to do that and its a meaningful use of your companies time then it can work well for you. But you need to have clear-eyes to see what you’re facing.

A huge thanks to José Valim, Lance Halvorsen, Jeff Weiss, Greg Mefford, Neil Menne and others for reviewing this post.